An annulment and a divorce are both ways of achieving a legal separation from a spouse. But there are subtle yet important legal distinctions between the two.

These distinctions can sometimes make a big difference, including what property rights a spouse may have, and how a spouse may have to pursue getting custody of children. This post will cover when a marriage is eligible, what the process looks like, and what the implications are going forward.

Table of Contents

- Annulment vs Divorce: Impacts

- What Are Grounds for Divorce?

- How Do I Get an Annulment?

- Key Differences Between Annulment and Divorce [Table]

- Religious Annulment

- Video

Annulment vs. Divorce: Impacts

At the most basic level, an annulment is a court declaration that a marriage is invalid, while a divorce is a court declaration ending a marriage. The key difference is that an annulment specifies that a marriage was never valid to begin with, and makes it as though the marriage never took place. A divorce, on the other hand, is used when a marriage was validly entered into, but is ending because of the choice of one or both spouses.

Financial Impacts

Separating can have a significant impact on a couple’s finances. This is particularly true for those with ample assets or complicated financial situations. Because the financial consequences of annulments and divorces are different, there may be situations where one process could be simple and the other much more complicated.

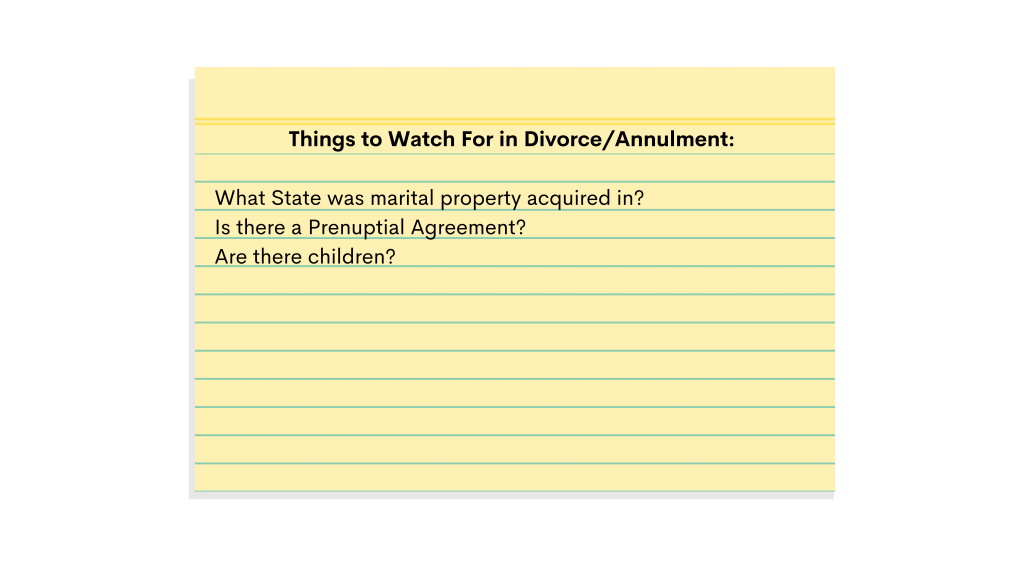

In a divorce, the primary consideration for how assets will be divided is where the couple is living, or where they were living at the time a particular piece of property was acquired. Different states have different rules regarding how a couple’s property should be divided, but for the most part, unless the spouses have a premarital agreement, or are able to agree on how all of their assets should be split up, a court will ultimately have to make hard decisions, which one or both spouses may resent.

With an annulment, by contrast, because the process means that a marriage was never valid to begin with, courts are less likely to tie together a couple’s assets, and are more likely to try to restore each spouse to the positions they were in before the marriage began. But there are exceptions, including “putative spouses,” discussed below.

Community Property States

In the case of marriages in what are called “community property states,” all assets acquired during a marriage are considered “community property,” meaning that they belong to both spouses, and will be divided equally during a divorce. There are nine community property states.

In the case of an annulment, there is no community property because the marriage never existed. Likely because annulments tend to happen more quickly after a marriage has begun than divorces do, there is comparatively little statutory guidance or case law about assets and debts acquired during a marriage are split up in community property states. But in general, courts are expected to divide them evenly. But spouses should keep in mind that this can be difficult in situations in which a couple has acquired a sizeable or complex asset that is not easily divided, like a house or ownership of a company.

Equitable Distribution

All states that do not rely on community property rules in case of divorce use what is known as equitable distribution of marital property, sometimes called equitable division. Equitable division is less strict than community property. It empowers a judge to divide a couple’s assets in a “fair” manner, but what this means varies widely by state. Most states will have statutes that provide a judge with factors that the judge is to use in deciding what is fair or equitable.

As is the case with a community property state, an annulment simplifies things in an equitable distribution state, because legally there is no marital property to distribute.

Prenuptial Agreements

Prenuptial agreements are legal documents that enable spouses to decide how their assets will be divided in the event of divorce (or death). Prenuptial agreements — often called premarital agreements, antenuptial agreements, or simply prenups — are an option in every state, and are especially recommended for those with complicated asset portfolios.

Only 5% of couples have a prenuptial agreement in place to protect their assets if they divorce.

Prenuptial agreements trump whatever a state’s default rules are for the division of assets, and in cases of divorce will apply regardless of whether the property was acquired in a community property state or an equitable division state. But they do not come into play if a couple obtains an annulment. Prenups become effective when a couple gets married, not when they are signed, and because an annulment means a marriage technically never took place, it is as though the prenup never became effective.

Spousal Support

Payments made to a former spouse after the conclusion of a marriage are known as spousal support, sometimes called alimony. Conditions on spousal support, such as a required amount that one former spouse is obligated to pay each month to another, are commonly set by a judge as part of a divorce proceeding. They may also be determined, with some limitations, through a prenuptial agreement.

In the case of an annulment, because the marriage is thought to have never existed at all, courts generally cannot grant permanent spousal support. However, a judge may impose temporary spousal support for a defined period of time.

Note that spousal support is distinct from child support, which is discussed in the “Child Support and Custody” section below.

Putative Spouses

In some states, it’s possible for a marriage to be invalid and eligible for annulment, but for a court to nonetheless find reason to grant some level of spousal support or some marital property rights. This is usually done out of the same ideas of “fairness” or “equity” that motivate community property and equitable division, but legally, it happens for a different reason: the “putative spouse” doctrine.

A putative spouse is a person who entered into a marriage that one or both spouses believed to be valid but which for some reason is not. In some cases, both spouses may have an incorrect belief; for example, a man may believe his spouse from a past marriage has died, and that he is now free to marry again, only to discover after getting remarried that the past spouse is still alive. In others it may involve one spouse deceiving the other; for example, a man may claim that he has been divorced from a past spouse, when he knows he has not.

In either case, there are at least three requirements:

- There was an official marriage ceremony, and the spouses live as a married couple

- One or both spouses considers the marriage valid

- There was some problem with the marriage of a kind that made it invalid

If one spouse seeks and obtains an annulment, the other spouse may petition to be recognized as a “putative spouse” and receive some share of the marital property. In general, community property states are more likely to grant some recognition of property rights to a putative spouse. States that recognize rights of putative spouses, either in statutes or in case law, include:

- California

- Colorado

- Illinois

- Louisiana

- Minnesota

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- Washington (uses the term “committed intimate relationship”)

Law on this subject can be confusing, and in many states is unclear or undetermined. Those with concerns about being in a putative spouse situation should consult an attorney.

Common Law Marriage vs. Putative Marriage

Putative spouses are different from “common law marriages,” which are recognized in some states. Common law marriages involve couples who share many of the characteristics of married couples, but never conducted a formal marriage ceremony.

For someone to be a putative spouse, the person must have taken part in what seemed to be a formal marriage ceremony. Adding to the confusion, some states recognize both common law marriages and putative marriages, and treat their rights to marital property differently.

Child Support and Custody

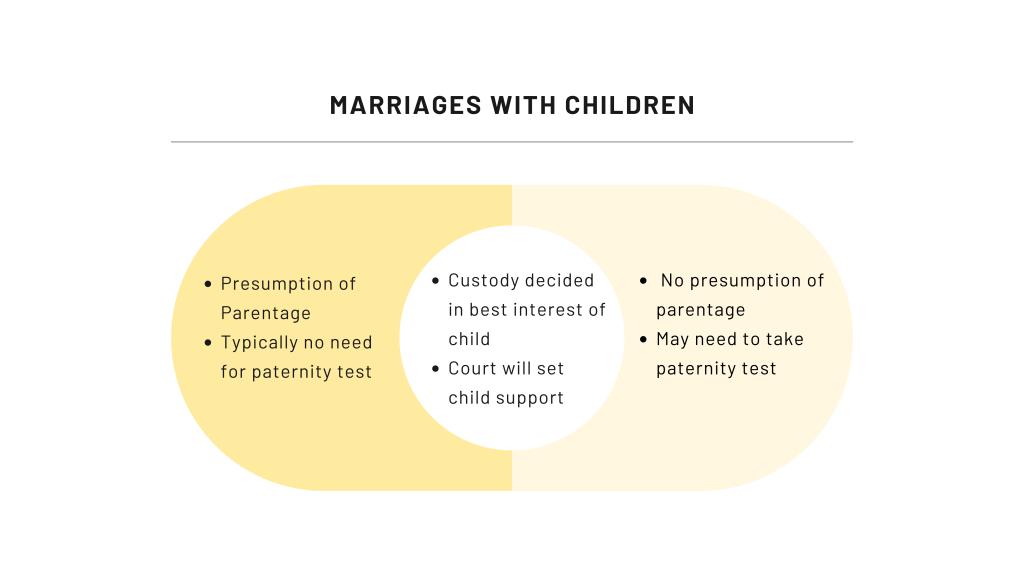

When a child is born to a married woman, the child is automatically considered to be the child of the spouses. This is known as the martial presumption of parentage, sometimes called the marital presumption of legitimacy.

In the case of a couple with one or more children getting a divorce, the martial presumption means that a court will decide on custody arrangements between the parents. Custody decisions are some of the most challenging and emotional inquiries a court can make. Although law varies from state to state, the general criteria is to make custody decisions in the best interest of the child.

Once this has been decided, the court will decide how, if at all, to impose a child support obligation. Like spousal support, child support is an obligation paid by one spouse to another. Although state laws vary on the subject, most use the Income Shares model, in which the court will try to replicate the level of support that the child had when the couple was together. Unlike spousal support, prenuptial agreements generally cannot be used to block child support obligations.

In the case of an annulment, because the marriage is considered never to have taken place, a child’s father will need to establish paternity in order to be eligible for custody and support. The means of establishing paternity vary from state to state; in some cases, a medical test may be necessary, while in others, simple acknowledgement may be enough. Because establishing paternity in disputed cases can be complicated, seeking the assistance of an attorney is advisable. In some states, the division enforcing child support laws of the state attorney general’s office may be able to offer free assistance.

What Are Grounds For Divorce?

A no-fault divorce means there is no need to prove any wrongdoing, such as adultery, abuse, or abandonment, in order to legally dissolve a marriage. When New York allowed no-fault divorces in 2010, they became the final state to do so. However, states usually have a minimum amount of time that couples must be married before being able to file for divorce. In some cases, couples may even have to wait for years.

Unlike an annulment, anyone legally married in the United States that wishes to get a divorce is able to do so. In most states, a no-fault divorce can be filed by one spouse even if the other spouse does not agree to divorce.

How to Get an Annulment

An annulment involves filing with a court, usually the court in the county where the spouses are residing. In some states, there may be special family law courts to handle these petitions.

Like getting a divorce, it is possible to obtain an annulment without an attorney. In general, the cases that do not involve a dispute between spouses, sometimes called “uncontested,” are easier to resolve without an attorney.

Reasons a Marriage May Be Annulled

The criteria for getting an annulment vary from state to state. But there are a few reasons that appear in many states:

- Fraud/coercion – someone may have been conned into entering the relationship, or one or both spouses entered the marriage under duress

- Incest – marriage between close relatives

- Incapacitation – If one or both spouses was mentally incapacitated and was legally unable to consent to the marriage, such as if an individual was under the influence of drugs or alcohol or possessed an incapacitating mental illness

- Concealment – one or both spouses may have concealed major issues such as a criminal record, sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy by or with another, etc.

- Bigamy – one spouse was already married

- Underage marriage – one or both spouses were not of legal age to marry

- Citizenship – a spouse got married as a “ruse” to receive citizenship

Statute of Limitations

Many people believe that if a marriage has lasted only a short amount of time, it may be annulled simply because of its brevity. This is not the case — one of the above factors must also be met.

However, the inverse may be true: A marriage may become ineligible for annulment, even if one or more of the above factors is met, once a certain amount of time has passed. This notion of being prevented, or “barred,” from filing a lawsuit because of the passage of time is known as a statute of limitations.

States have varying time limits for seeking an annulment. In some states, there may be only a few months available to seek an annulment.

The statute of limitations may also vary within a state depending on the reason the annulment is sought. Those seeking an annulment because one or both parties was under the age of consent at the time of the ceremony, for example, usually must file for an annulment within a certain amount of time of the spouse turning 18.

Key Differences Between Annulment and Divorce

Annulment |

Divorce |

|

| Marital status | Single | Divorced |

| Did the marriage exist? | No | Yes |

| Time before ability to file | None | Varies, could be years |

| Division of property | No | Yes |

| Reason/proof required | Yes | No (no-fault) |

Religious Annulment

The references in this post to annulment refer to legal proceedings in a U.S. court of law. However, some religions have a separate annulment process that may be necessary to enter a successive marriage in the eyes of the faith.

These criteria may resemble from those recognized under the law of a particular state. Confusion often arises because the process for granting or denying an annulment in a particular faith may resemble a legal process. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, for example, outlines a “tribunal process” that is necessary to obtain a declaration of annulment.

Uncertainties about the impact of seeking a divorce or an annulment are best addressed with a faith leader, rather than the attorney for a legal proceeding.