In the not-so-distant past, the things people left to friends and family after passing on were things: cars, paintings, baseball cards, country houses. These days, however, it is increasingly common for the estate planning process to feature items that can’t be wrapped in paper or measured in acres: digital assets. Although there is significant uncertainty around future regulation of certain categories of digital assets, they are projected to become an ever-more common and important share of wealth for families and individuals.

This trend raises important questions with big implications for those who already own digital assets, and those who are thinking about investing in them and using them as the basis of an estate plan. How will these new kinds of assets change the estate planning process? Thankfully, existing estate planning tools like wills and trusts remain well-suited to handle these new kinds of assets. But there are some issues owners of digital assets should keep in mind.

Table of Contents

What Are Digital Assets?

“Digital assets” is a vast and ever-evolving category, one whose size reflects the increasing portion of modern life spent on the Internet. Broadly, anything of value that is not tangible, and recorded electronically rather than on paper is a digital asset.

Almost every state has enacted the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Assets to Digital Assets Act, an effort to standardize approaches to digital asset management. A “fiduciary” is someone who is charged with acting in the best interest of another, and the act empowers them to manage these assets, and allows the companies that serve as the assets’ custodians to deal with the fiduciaries. For purposes of estate planning, the fiduciary will likely be either a designated representative, the executor of a will, or a trustee, but the act also covers agents in powers of attorney, as well as conservators and guardians.

States also have their own laws on the subject, but neither these laws nor the Uniform Act gives special rights to digital assets to friends or family members. And even in states that have adopted the Uniform Act, the companies that oversee the digital assets still have to follow privacy laws that may prevent them from granting access to those who may benefit under a will or a trust. For these reasons, it is important to follow some basic guidelines when considering how to pass on digital assets:

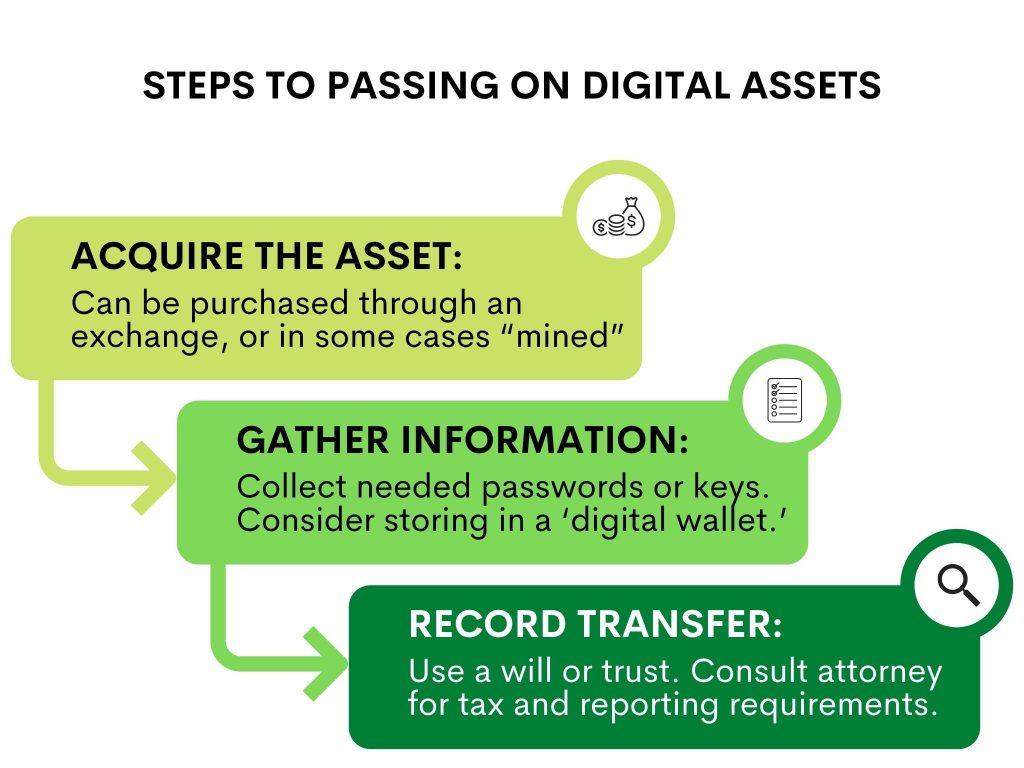

- Create a List: A written record of all of an estate’s digital assets will be important after a decedent has passed on. Here is a sample that can be filled in, or used as inspiration for a personalized list. It is essential that the decedent, along with identifying a digital asset, include all necessary passwords. It may be advisable to use a password management system to keep track of a large number of passwords and reduce the likelihood of being “locked out” of an asset

- Verify Access: After a list has been created, verify where each asset “exists.” While most will be accessible anywhere through “cloud” computing or web portals, it’s possible that some assets, such as written documents, exist only on a device’s hard drive. These should be transferred to a secure server, or if not, arrangements should be made to otherwise provide access. Some types of digital assets have multiple levels of encryption, or have different access requirements depending on the device through which a user seeks access. Those planning estates should test that the intended beneficiary of a digital asset is able to access it.

- Record Transfer: As in other types of estate planning, it is essential for decedents to memorialize their intentions in writing. The two most common types of estate planning documents are wills and trusts. Both may be used to transfer ownership of a digital asset. For wills, if important information about the assets is included, it may be advisable to document desires for digital assets in a separate document, known as a codicil. Unlike trusts, wills are generally public records. and most decedents don’t want to include sensitive information, like passwords, in such documents. It is also easier to update in case of modifications, like a change in passwords.

Personal Digital Assets

There are some special considerations that come into play with what are known as personal digital assets.

Photos and Documents

Uncertainty about photos and documents can be avoided by putting them in an account or folder that is accessible by heirs or beneficiaries before the owner passes on. If this is undesirable for some reason, the asset may be conveyed through a traditional estate planning document; just be sure to follow the steps above to ensure access.

Social Media and Email Accounts

Ongoing, password-protected services like social media and email are one of the most challenging types of digital assets to manage after death, in part because different companies have different policies about what they will and will not permit. As part of the list creating process, it’s important to look into the policies of the company that acts as custodian of a particular asset.

For example, Google has an “Inactive Account Manager” that allows people to name a “trusted contact” that can modify an account after a designated period of inactivity; this feature applies to the suite of Google applications, including Gmail, Drive, and YouTube.

Facebook, on the other hand, gives less power to people to manage the accounts of others. The accounts of those who die become “Legacy Accounts,” and account holders are able to name a “legacy contact” who can write posts and request the removal of the account, but can’t perform many functions, including reading messages, or adding and removing friends.

Electronic Entertainment

Although a person may have paid for digital forms of entertainment — such as music, books or movies — during their life, many companies restrict how these assets may be shared. It’s advisable to consult the Terms of Service to ensure that the asset may be managed or shared by another person.

Digital Investments

Facebook accounts, digital photos, and personal blogs all have some value. They aren’t valuable in the same sense as a stock or bond or money, though, because they can’t be easily exchanged; these assets are probably far more valuable to the people they involve than they are to the general public. Other types of digital assets do fulfill this definition. It’s long been possible to pass on non-physical assets like stocks, bonds, or an ownership stake in a company. And many assets are accessible and transferable through computers, such as funds in a bank account.

Things grow more complicated with a new class of digital assets that is much closer to traditional wealth, but operate outside the banking system: digital investments or blockchain assets. For potential investors, the biggest advantage of these assets is that they can be transferred instantaneously, in a market open to theoretically the whole world, with complete privacy and no cost other than computer processing power. But because they exist only in coding, and operate outside the well-regulated banking industry, they pose a challenging security issue: How is it possible to tell who owns what, or to make sure that sales of digital assets are not duplicative or fraudulent?

This is a serious concern for an investor, and for the heir to an estate or the beneficiary in a trust. The security risks behind digital assets vary considerably, and the future of government regulation — and even the ability of government agencies to do so if they wanted to — is uncertain, and should be a consideration in estate planning. But while there have been instances of hacking and theft, these have happened through targeting other technology, like password verification, not breaches of the underlying blockchain idea.

What is Blockchain?

The problem of ensuring that a digital asset is unique and secure, while also being universally accessible, is an example of what is known as the “distributed consensus” problem, which involves maintaining agreed-upon data among many independent computers, and has stymied computer scientists from the earliest days of the Internet. The solution to the problem came in 2008, with the development of Bitcoin, a system of peer-to-peer payments using digital tokens.

Rather than rely on a financial institution to assure that a transaction was valid, Bitcoin would rely on what has come to be known as blockchain technology. The workings of blockchain are complicated and rapidly evolving, but it essentially involves including a “block” of data about an asset at a given time, and including all of those blocks in a “chain” that follows the asset. The computing power of every computer involved in the network would validate a blockchain to ensure that an asset was not being fraudulently sold or transferred.

Blockchain investments the importance of organized estate planning for digital assets. Because they operate outside the banking system and frequently market themselves as valuing privacy above all, it is imperative to ensure that passwords and necessary encryption keys are provided ahead of time. Unlike social media accounts, in which the asset’s custodian has some interest in the link between the asset and its creator, the companies behind blockchain assets are focused only on security, and pleas from a relative or beneficiary are likely to go nowhere. There are many stories of people losing access to hundreds of millions of dollars worth of digital assets after dying, or even while alive if a device is accidentally thrown away.

Cryptocurrency

Cryptocurrencies are among the most popular applications for blockchain technology. As the name indicates, they are currencies whose secure value comes through encryption rather than governmental authority, and act as a medium of storing, measuring, and transferring wealth. Cryptocurrencies can be bought, sold, traded, loaned, and used in financial transactions that mirror those in the world of traditional finance. Although these opportunities are expanding, opportunities to use cryptocurrency in everyday life, such as buying a meal at a restaurant, remain limited. Instead, much of the interest in cryptocurrency appears to come from those intending to hold the coins for long-term gain, making them more like a stock than conventional cash.

This can make them attractive to people looking for ways to use their money to create an estate that can be passed on in a will or trust, but also leaves cryptocurrency subject to potentially heavier government regulation. The financial uncertainty posed by the pandemic, and more recently spiking rates of inflation in many counties, has encouraged explosive growth in cryptocurrency investing. By the beginning of 2022, the global market capitalization for cryptocurrency exceeded $2 trillion, a total that at times increases by as much as 3 percent per day. As the New Year arrived, bitcoin was trading at more than $43,000 per unit. (The cryptocurrency bitcoin is not capitalized; “Bitcoin,” with a capital B, is the name for the peer-to-peer transfer system.) Although this is down from earlier valuations in excess of $60,000, it’s also an immense increase over the past five years, when a single bitcoin traded for less than $1,000.

To protect these valuable assets and ensure that they may be passed on, some are turning to “digital wallets,” services that store and organize cryptocurrencies and other digital assets. Some exchanges, like Coinbase, maintain wallet applications that enable family members to contact them about a deceased relative’s crypto assets

NFTs

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, are another type of digital asset dependent on blockchain technology. It is a property of any currency that each unit is considered exchangeable for another or collection of other units, so long as the total value is the same; for example, a person should be indifferent between receiving two $5 bills or one $10 bill. NFTs, on the other hand, are “non-fungible” in the sense that each one is unique; they are not as easily replaced, because they are associated with a specific thing, such as a photo or video. Popular types of NFTs include works of art and clips of athletic performances, with blockchain being used to verify that the image or video is unique.

Even more so than cryptocurrency, NFTs face uncertainty about how they should be treated by the government. The government has long used something known as the Howey Test for determining whether a given transaction qualifies as a “security,” which would make it eligible for regulation like a stock. Whether NFTs qualify is still uncertain. The expectation of many holders of NFTs to profit from them over time, and the ability to sell off pieces of an NFT through digital exchanges indicates that they should be thought of more like stocks; others argue that the attachment to the image or video associated with an NFT means they should be considered more like buying an antique or a work of art, something that may be thought of as an investment but which face fewer regulations.

Many people in the financial industry are awaiting indications of how the government will treat NFTs. The decisions will ultimately impact families and estates, including changes to potential tax liabilities, and obligations to disclose investment information. If either of these is a make-or-break proposition for an estate plan, it may be advisable to consider a different class of assets.